Can Transcription Factors Turn Back the Clock on Aging?

A Regulatory View on Longevity, Epigenetic Reprogramming, FOXO3, and Human Progeroid Syndromes

For most of human history, aging was treated as fate.

Wrinkles, frailty, declining resilience — all seen as unavoidable consequences of time.

But what if aging is not primarily about broken parts?

What if it is about lost regulatory control?

Modern longevity research is converging on a powerful idea: aging is driven not only by molecular damage, but by progressive misregulation of gene expression. And at the center of this control system stand transcription factors — the molecular decision-makers that determine which genetic programs are active, suppressed, or over-activated across a lifetime.

In this regard, aging is less like a machine wearing out, and more like a complex system drifting away from stable regulation.

And that is a problem biology may be able to solve.

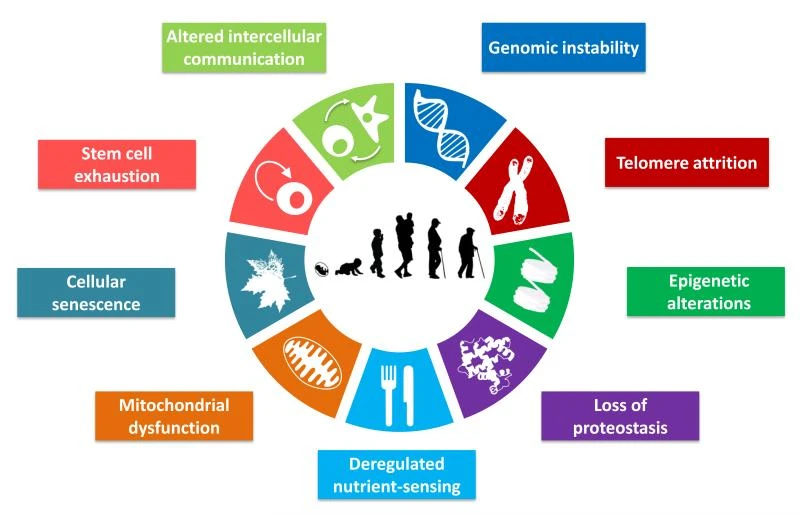

Figure 1 below illustrates these hallmarks, from genomic instability and senescent cells to stem cell exhaustion, all contributing to the progressive decline we recognize as aging. No single gene controls all of this – instead, aging emerges from the breakdown of many systems in unison.

Science Fiction to Systems Biology

Only a decade ago, reversing aspects of aging belonged firmly to science fiction.

Today, it is being tested in laboratories.

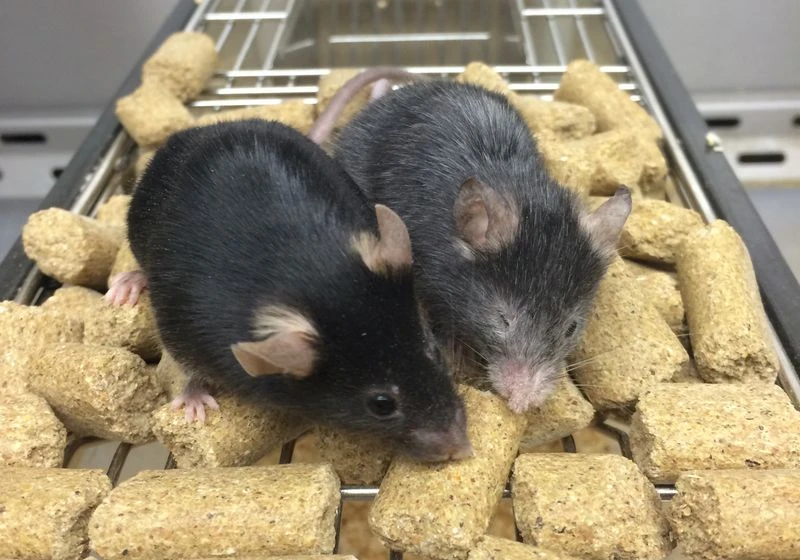

In 2023, researchers associated with Harvard demonstrated that aging in mice could be accelerated or partially reversed by manipulating epigenetic information — the regulatory layer that controls how genes are used without changing DNA sequence. By first scrambling and later restoring this regulatory “software,” the scientists observed rapid aging followed by measurable rejuvenation.

The implication was profound.

Cells appeared to retain a latent memory of youth — a reference regulatory state that can, under specific conditions, be partially restored. Aging, in this framing, is not merely cumulative damage, but a loss of regulatory coherence.

If this is true, longevity will not be achieved by replacing parts, but by stabilizing gene regulatory networks.

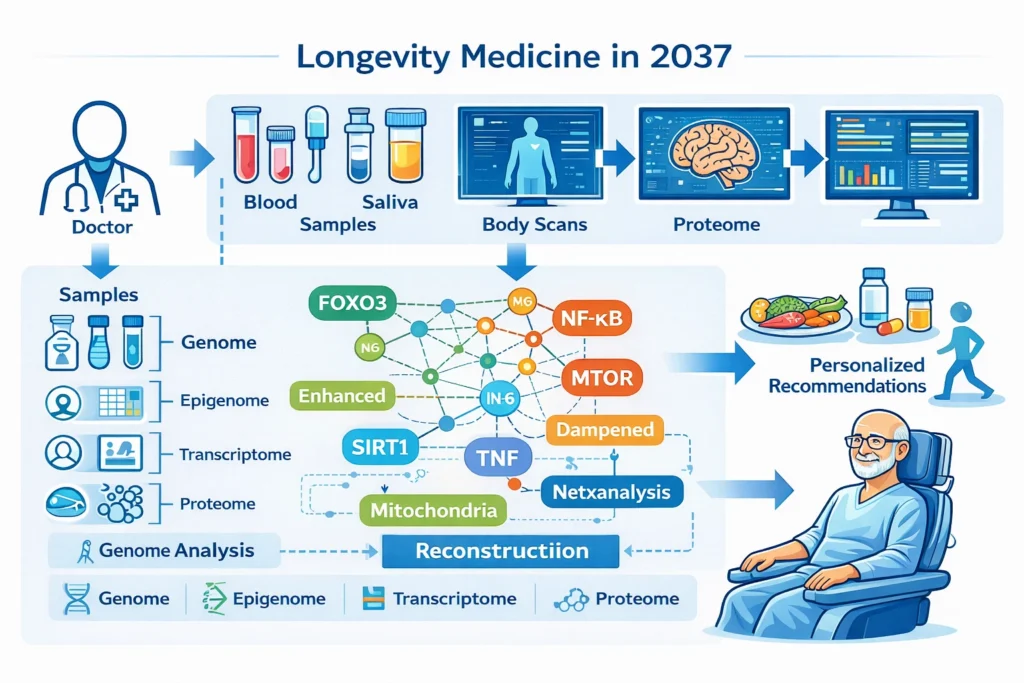

A Near-Future Scenario: Longevity Medicine in 2037

Imagine a clinic in the late 2030s. A patient does not receive a single “anti-aging drug.”

Instead, their genome, epigenome, transcriptome, and proteome are analyzed together.

An AI-assisted systems biology platform reconstructs the patient’s gene regulatory networks, identifying which transcription factors have shifted into aged states, which stress-response programs are weakened, and which inflammatory circuits are chronically over-activated.

The intervention is not a global reset. It is a precision regulatory correction.

Perhaps FOXO-mediated stress resistance is enhanced. Perhaps chronic NF-κB-driven inflammation is dampened. Perhaps mitochondrial quality-control programs are restored.

Aging is no longer treated as an inevitable decline. It becomes a dynamical system that can be stabilized.

Not immortality — but controlled longevity.

Aging Is a Systems Problem, Not a Gene Problem

Aging is not caused by a single gene or factor.

It is a multi-layered, interconnected process involving nearly every level of biology.

Researchers often describe aging using the hallmarks of aging, including:

These hallmarks describe what goes wrong — but not who controls it.

Behind every hallmark lies gene regulation: genes being activated too weakly, too strongly, or at the wrong time. And gene regulation is governed by transcription factors, chromatin modifiers, and signaling pathways.

This is where longevity research shifts from description to regulatory logic.

Transcription Factors: The Control Layer of Aging

Transcription factors do not encode enzymes or structural proteins. They encode decisions.

They integrate signals from nutrients, hormones, stress, DNA damage, and metabolism — and translate them into genome-wide programs of gene expression.

With age, these decision systems drift:

This drift is neither random nor purely stochastic.

It reflects changes in transcription-factor activity and epigenetic accessibility.

Among all regulators studied so far, one stands out repeatedly across species and human populations: FOXO3.

FOXO3: A Master Regulator of Longevity

FOXO3 is one of the very few genes consistently associated with exceptional human longevity across populations. Variants near FOXO3 are enriched in centenarians — but FOXO3 is not a “longevity switch.”

Its importance lies in its network position.

As a transcription factor, FOXO3 coordinates entire protective programs:

FOXO3 integrates inputs from insulin/IGF-1 signaling, nutrient availability, oxidative stress, and energy balance — and decides which survival programs are activated.

In regulatory terms, FOXO3 is a master regulator — not because it acts alone, but because it controls many aging-relevant pathways simultaneously.

You can find more information on FOXO3 in our other blog here:

https://genexplain.com/foxo3-key-regulator-in-aging-and-longevity/

FOXO3 is just one transcriptional regulator; many others (such as NRF2 for oxidative stress, NF-κB for inflammation, mTOR for nutrient sensing, and the Yamanaka factors for cell identity) play pivotal roles in aging biology.

The common thread is that regulatory networks – circuits of transcription factors, signaling proteins, and epigenetic modifiers – decide the cell’s fate under stress and time.

By reconstructing these networks, scientists hope to identify which “nodes” are the best intervention points to slow aging.

Epigenetic Reprogramming: Editing the Regulatory Software

Epigenetics defines which transcription-factor binding sites are accessible and which regulatory programs can run.

DNA methylation, histone modifications, and chromatin structure act as a dynamic interface between transcription factors and the genome.

Partial epigenetic reprogramming experiments have shown that restoring youthful chromatin states can reverse functional decline in animals without changing DNA sequence. A landmark experiment by Ocampo et al. showed that inducing Yamanaka factors (a set of four genes that can turn cells into stem cells) for short durations in mice reversed certain aging signs without causing cancer.

More recently, in 2020 and 2023, studies from David Sinclair’s lab provided evidence that epigenetic changes are a cause of aging, and restoring youthful epigenetic information can reverse aging in mice. In one study, researchers introduced targeted DNA breaks to scramble the epigenome of young mice – and the mice began to exhibit premature aging (gray fur, frailty, organ damage) while their DNA sequence remained intact. Amazingly, by re-activating certain developmental genes (essentially “reinstalling” the original epigenetic software), the team rejuvenated those mice, recovering tissue function and even restoring vision in old mice. These experiments suggest that cells retain a backup copy of youth – a reset program buried in their DNA that, if triggered correctly, can roll back many years of molecular wear-and-tear. The challenge now is finding safe ways to achieve partial reprogramming in humans.

Importantly, epigenetic modulation is not limited to genetic engineering. Certain natural compounds — such as resveratrol, a plant polyphenol — influence chromatin regulation and transcription-factor activity via SIRT1 and FOXO-related pathways. These compounds do not “reset” cells, but act as regulatory nudges, subtly reinforcing stress-resilience programs.

This highlights a continuum of intervention strategies — from lifestyle and dietary signals to targeted epigenetic editing — all converging on transcription-factor control.

Caloric Restriction and Longevity Drugs: Metabolic Control of RegulationOne of the most robust lifespan-extending interventions across species is caloric restriction (CR). Reducing caloric intake activates conserved survival programs that enhance DNA repair, autophagy, antioxidant defense, and metabolic efficiency.

At the regulatory level, caloric restriction:

Because long-term caloric restriction is difficult in humans, researchers are developing CR mimetics — drugs that reproduce similar regulatory states.

Key examples include:

Crucially, these interventions do not target single genes.

They reshape regulatory programs, reinforcing resilience networks that slow aging.

Werner Syndrome: A Human Model of Regulatory Failure in Aging

One of the most compelling pieces of evidence that aging is a regulatory problem comes from Werner syndrome (WS) — a rare human progeroid disease.

Werner syndrome is caused by mutations in the WRN gene, which encodes a RecQ helicase involved in DNA repair, replication, and telomere maintenance. Patients with Werner syndrome develop features of accelerated aging: genomic instability, premature graying, osteoporosis, atherosclerosis, and cancer predisposition.

At the molecular level, WRN interacts with key components of:

Loss of WRN function disrupts regulatory coordination between DNA repair, replication, and telomere maintenance — leading to systemic aging phenotypes.

Werner syndrome demonstrates something crucial:

aging-like decline can arise not from random damage alone, but from failure of regulatory integration.For this reason, Werner syndrome serves as a powerful human disease model of aging, and we will provide detailed WS pathway and regulatory reports as a lead magnet in this series.

Cracking the Longevity Code with Regulatory Genomics (The TRANSFAC Perspective)

Untangling the complexity of aging requires more than cataloging gene expression changes—it demands uncovering the upstream regulatory mechanisms that drive them. That’s where geneXplain’s systems biology approach excels. By analyzing large-scale datasets—such as expression profiles from young versus aged cells or long-lived versus typical organisms—we reconstruct the regulatory logic that governs these shifts. Our aim is not just to observe what changes, but to pinpoint why it changes.

To achieve this, geneXplain integrates proprietary multi-omics data with expertly curated regulatory networks, building computational models that map the architecture of aging at a systems level. This enables the discovery of key regulatory motifs and combination targets with potential to modulate lifespan—bridging the gap between data-rich biology and actionable insights in gerontology.

Using resources like TRANSFAC and TRANSPATH, our platform identifies transcription factors and signaling molecules—such as NF-κB or FoxO3—that repeatedly emerge across age-associated genes. By tracing these signals back through their upstream cascades, we build causative networks that reveal master regulators—the true drivers behind the molecular changes of aging.

Rather than focusing on downstream effects, we prioritize these statistically enriched regulatory hubs, including transcription factors, kinases, and microRNAs that govern entire biological programs. This strategy allows researchers to generate targeted, testable hypotheses for aging interventions—opening a path to more precise, multi-dimensional longevity strategies.

From Treating Aging to Engineering Stability

Longevity research is entering a new phase.

The question is no longer whether aging can be influenced — that has been demonstrated repeatedly. The real challenge is precision: how to intervene safely, system-wide, and durably in humans.

The emerging answer is clear: Aging is a failure of regulatory coordination, and longevity is a problem of regulatory stabilization.

If aging is a corrupted program, transcription factors are the system administrators.

And decoding their logic may be the key not to immortality — but to extending healthy, resilient human life.

What’s Next

In the next part of this series, we will focus on epigenetic regulation and demonstrate how genome-wide DNA-methylation and expression data can be analyzed with Genome Enhancer to identify master regulators of aging — including FOXO3 and WRN-associated networks.

Stay tuned — we are only beginning to decode the regulatory code of longevity.

References:

- López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013 Jun 6;153(6):1194-217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039. PMID: 23746838; PMCID: PMC3836174.

- Nature Portfolio. 2024. “Ageing Is Driven by a Network of Regulatory Processes.” Nature Reviews. https://www.nature.com/articles/d42473-024-00359-x.

- Morris BJ, Willcox DC, Donlon TA, Willcox BJ. FOXO3: A Major Gene for Human Longevity–A Mini-Review. Gerontology. 2015;61(6):515-25. doi: 10.1159/000375235. Epub 2015 Mar 28. PMID: 25832544; PMCID: PMC5403515.

- The Scientist. 2022. “Epigenetic Manipulations Can Accelerate or Reverse Aging in Mice.” https://www.the-scientist.com/epigenetic-manipulations-can-accelerate-or-reverse-aging-in-mice-70888.

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. 2024. “Cell DEC.” NCBI Research News. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/search/research-news/16451/.

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. 2024. “Research News.” NCBI Research News. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/search/research-news/18098/.

- Lee, Sylvia. n.d. “Chromatin Transcriptional Regulation in Development and Longevity.” Sylvia Lee Lab, Cornell University.

- https://blogs.cornell.edu/sylvialeelab/research/chromatin-transcriptional-regulation-in-development-and-longevity/.

- “Identification of Master Regulators within the geneXplain Platform.” geneXplain GmbH, https://genexplain.com/identify-master-regulators/.